The Las Vegas-based gaming company angling to build a $50 million casino and hotel complex in New Haven faces some enormous challenges.

The biggest obstacles aren’t in northeast Indiana, however, where supporters and opponents alike reside.

The 2024 annual report Full House Resorts Inc. filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission discloses 55 ways the company is vulnerable.

The list includes:

• An economic downturn could reduce consumers’ discretionary spending

• Heavy reliance on technology and electricity could cripple the company in the event of a cyber attack or extended power outage

• It’s possible the operation won’t be able to generate enough cash flow to make loan payments on its “significant indebtedness.”

Although it’s common for companies to be vulnerable to recessions and cybercrime, they aren’t all burdened by debt that’s higher than the company’s value. Full House’s market cap – or the combined value of its shares – was about $175 million on Thursday.

Full House reported long-term debt of almost $480 million in the 2024 filing.

That amount is 68% of total company assets as of Dec. 31, 2023, when the company operated seven casinos. Full House’s long-term debt was 79% of total company assets if goodwill and other intangible assets are excluded.

Annual revenue reported for 2023 was $241 million.

The company also reported a $24.9 million loss for 2023, which was a 68% increase from the $14.8 million loss reported for 2022.

Ongoing operations

In 2022, Full House stock was trading at more than $12 a share on the Nasdaq stock market. Since fall 2023, the price has hovered around $5.

The company’s financial health is tied closely to the economy. Its stock price fell to below $1 in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001 and hovered at less than $2 a share during the Great Recession in 2008 and again during the coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

Among its outlined risks, Full House said it cannot guarantee that shareholders will be able to sell their stock at a favorable price – or find a buyer at any price. Also, outstanding stock options awarded to executives could result in more shares outstanding, lowering the value of each share owned by existing stockholders.

Full House executives aren’t the only ones who see the company’s vulnerabilities. An independent investing website recently found some, too.

Simply Wall St.’s mission “is to empower every retail investor in the world to make smarter, more confident investment decisions,” according to its website.

The firm’s company risk analysis of Full House found:

• Significant insider selling over the past three months

• The company is currently unprofitable and not forecast to become profitable over the next three years

• Shareholders’ equity in the company has been diluted in the past year

• The company has less than one year before the amount of cash on hand is fully depleted by its monthly operating shortfall.

Doing due diligence

New Haven Mayor Steve McMichael invested considerable effort in researching Full House before deciding to back the project, including looking into the company’s balance sheet, a colleague said. McMichael was unavailable for an interview this week, but he outlined his efforts in a column published Nov. 29 The Journal Gazette.

McMichael wrote that he visited 12 of the 13 Indiana cities that host casino operations. Zach Washler, the city’s community development director, accompanied McMichael on some of those trips. He said this week that stops included Anderson, Shelbyville, Terre Haute, Lawrenceburg and Rising Sun.

Rising Sun is the community that would lose its riverboat casino if the Indiana General Assembly votes to allow Full House to move its gaming license to New Haven – and if the New Haven City Council agrees to allow it after the proposal winds its way through the legislative process. The General Assembly session will end on April 29 at the latest.

Rising Sun officials didn’t return multiple messages The Journal Gazette left this week requesting comments on the impact of the Full House casino there. But officials, including the mayor, met with McMichael during his visit, Washler said.

McMichael wrote: “I looked for reasons to say ‘no’ to the development in New Haven. I looked for evidence of increased crime, addiction and poverty in these communities. I talked to local leaders including mayors, fire chiefs, police chiefs and leaders of local nonprofits. I asked them hard questions. And in every case, I didn’t see evidence of harm to those communities.”

“Local officials and nonprofit leaders all said the same thing. There was a negligible increase in crime, poverty or addiction attributable to the presence of a casino. The expected problems never developed,” McMichael wrote. “Rather, all local officials and leaders said the casinos are good corporate citizens that have helped the local community through philanthropy and economic development.”

That included in Shelbyville, where residents feared a new casino operated by Caesar’s Entertainment would lead to more crime. In response, the local police department created a task force to address the expected uptick. Officials told McMichael the task force was disbanded after six months because the increase never materialized, Washler said.

Various officials said the state’s strict gaming regulations have helped ensure that communities have a good experience, Washler said.

Indiana Gaming Commission officers are on-site at the state’s casinos, monitoring operations every day, he said, adding that gaming companies also employ security staff.

McMichael, in the November column, summed up this opinion by saying that he’s “all in” on hosting a casino.

“This fact-finding, coupled with the potential economic impact for New Haven, required that I bring this idea to the community for public discussion,” he wrote, adding that discussion has been robust and mostly positive.

Dollars and cents

The potential cash infusion for New Haven is difficult to ignore.

A study conducted by international consulting firm CBRE and commissioned by Full House projected that a proposed New Haven casino would generate more than $80 million in annual taxes and help create more than 2,400 new jobs.

The estimated breakdown would be $53.5 million in state taxes, $18.3 million in city taxes and $11.1 million in taxes for other local stakeholders, including Allen County and East Allen County Schools.

Tim Hines, president of the EACS school board, said this week that following a presentation by Full House representative, board members chose to remain neutral on the controversial subject despite the prospect of additional financial support for the district.

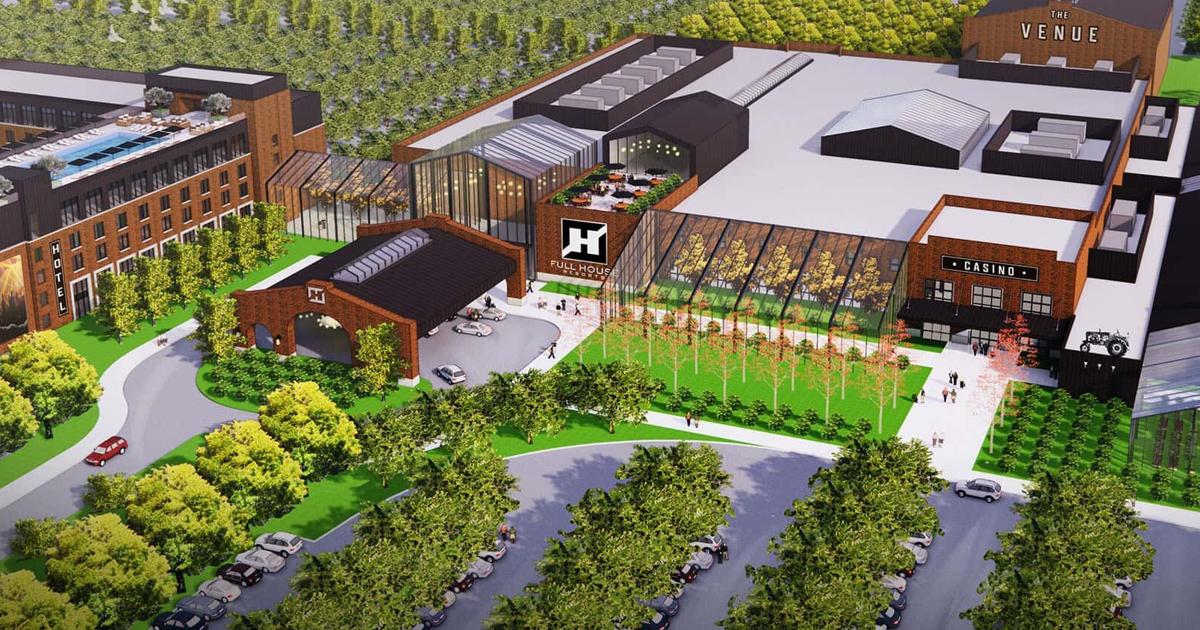

State Sen. Andy Zay, R-Huntington, this week filed a bill that would allow Full House to move its gaming license from its riverboat docked at Rising Sun in southeast Indiana to a $500 million tourist attraction that would include a 90,000-square-foot casino, a five-story luxury hotel, a prime steakhouse, a concert venue and more.

Senate Bill 293, which has an effective date of July 1, had its first reading Monday and was referred to the Committee on Public Policy.

The bill, as written, includes requirements for how some of tax money collected by the city of New Haven could be spent. It’s possible that amendments could be added to the final language – if it passes and is signed by Gov. Mike Braun.

New Haven would receive 25% of the taxes paid to the state; the remaining 75% would be combined with other state-collected gaming taxes and distributed to counties, cities and towns throughout Indiana, depending on population.

The bill specifies that at least 20% of New Haven’s total gaming revenue would be used to lower property taxes for those filing a homestead deduction on property in the city. New Haven Mayor Steve McMichael asked for that provision, Zay said, to ensure that property tax relief will continue for residents after he leaves office.

Senate Bill 293 also calls for creation of a group to oversee a portion of the taxes paid by the proposed casino – 3% of New Haven’s share. McMichael has publicly promised to contribute an additional 2% while he’s in office, Zay said.

A board designated as the Together for Tomorrow Commission would have four members: New Haven’s mayor, Fort Wayne’s mayor, the president of New Haven’s city council and one county commissioner, to be selected by the board of commissioners.

The commission would be allowed to use money in the fund for public health, public safety, addiction services including for gambling addiction, recovery services and resources; to address homelessness; or for any other purpose deemed appropriate by the commission.

McMichael provided a statement for this article on Friday.

“After careful research and visits to many Indiana casino communities, I am 100% confident that moving this conversation forward will bring lasting benefits to our current residents and future generations,” he said.

“With our plan, we will invest in social initiatives, student scholarships, property tax relief, and economic growth –building a strong, vibrant community for today’s residents and the next 100 years and beyond.”