The legalization and rapid spread of sports betting has made problem gambling everyone’s problem.

Like fishermen and romantics, gamblers never forget the one that got away. For Rob Minnick, now 25, that was in 2018, during the annual “March Madness” college basketball tournament. Early in the competition, the underdog Retrievers of UMBC (that’s University of Maryland, Baltimore County) beat the favored Virginia Cavaliers in a massive upset. It was the first time in college basketball history that a 16th-seed team (for non–sports fans, that’s the worst, lowest-ranked team in its geographical region) had defeated a first-seed favorite. And Minnick felt like an idiot for not having laid money on it. “Worse than losing a bet,” he says, “is not making a bet that you would have won, and feeling regret about it. I was like, ‘That was obvious,’ even though it had never happened before.”

So Minnick took all his money and put it on the Retrievers in their next game. They lost, falling to the Kansas State Wildcats 50–43. Scrambling, Minnick finagled some credit and bet on a New York Yankees preseason exhibition game. He missed again. Out of money and in deep with a black-market bookmaker, he turned to his family for help. “I never said I had an addiction,” he recalls. “I just said I bet too much. They bailed me out with the bookie. I worked two jobs that summer to pay them back. And that cycle just kept repeating.”

Growing up in Philadelphia, Minnick was used to feeling like the world revolved around sports: The city’s four major professional teams were the core of his social and family life. During autumn and early winter—that is, football season—family get-togethers took place on Sunday afternoons so the Eagles game could play in the background. By the time he turned 18, Minnick and his friends were taking part in daily “fantasy sports” contests, wherein users string together a number of guesses (or “pick’ems”) on player performance (over or under a certain number of receiving yards, rebounds, or at-bats, for example) in hopes of winning cash prizes. “We can make money doing what we’re already doing?” Minnick remembers thinking. “It was a no-brainer. We were hooked. Well, ‘we’ meaning… mainly me.”

But it wasn’t just him. Once upon a time, the words “gambling addict” may have conjured images of an old man at the track fumbling for betting slips in his raincoat pockets, or a blue-haired woman sitting for hours at a slot machine, flagging down a cocktail waitress for complimentary watered-down gin and tonics. But a 2024 study found that “problem behaviors” related to gambling were most prevalent among young men between 18 and 30 years old.

After Minnick turned 21, his gambling habit quickly spiraled. Months after his March Madness crisis, in 2018, Pennsylvania had begun expanding legal sports betting and other forms of gambling for adults over the age of 21, both at “retail” locations (such as casinos) and online. Minnick went from betting on games he watched to playing blackjack and slots on his smartphone via a range of licensed, regulated apps that defined the new legalized-gambling landscape. At one point, he was blindly pressing the “Spin” button on a digital slot machine, calculating how much money he was making (or losing) by the sounds piped in through his headphones. There was no longer any need to entrust his money to black-market bookies; the game was changing. And it still is. Sports, politics, and culture are being recast in terms of wagers, probabilities, over-unders, and other betting slang. It is a process that is reshaping the experience of American life in the 21st century. Call it gamblification.

This new gambling marketplace found itself with a new target demographic during the Covid-19 pandemic: a population sample of bored, isolated people, many receiving money from the government and looking for something to spend it on. As the global sports (and sports betting) landscape started to open up, Minnick took his $600 stimulus check and used it to bet on South Korean baseball, which he had never watched in his life. In 2022, he hit a sizable payday and used the money to visit a woman he knew in Paris. Within two hours of his arrival, he found himself perched on the toilet in his Paris hotel, blowing all the money he had saved on digital baccarat. “That’s when I said, ‘OK, maybe I have a gambling problem,’” Minnick told me, sitting outside Philadelphia’s stately City Hall in a 76ers cap, while an ad for the FanDuel sports-betting platform played on a nearby billboard.

“Gambling,” the late comedian and noted problem gambler Norm Macdonald once said, “is a disease… but it’s the only disease that can make you very wealthy.”

Until fairly recently, that disease, though it had never been eradicated, had been contained by a kind of legal quarantine. Anyone looking to lay a lawful bet on a championship game, or savor the turn of the card, the roll of the dice, the spin of the proverbial “big wheel,” once had to travel to places where it was legal to do so: Las Vegas, Atlantic City, or the casinos owned by Native American tribes. The 1992 Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) outlawed sports betting federally. There were a few notable exceptions—dog racing, for example, and, for some reason, jai alai—but for fans of mainstream sports, there was considerable “friction,” as addiction experts call it, on the path between the desire to gamble and the ability to actually do it.

In 2018, after years of legal challenges spearheaded by the state of New Jersey, the Supreme Court ruled that PASPA violated the 10th Amendment of the US Constitution, which guarantees that states may make determinations on rights that are not explicitly protected by the federal government—including the regulation of gambling. It may be hard to believe now, after most professional sports leagues have struck up official partnerships with sports books and casinos, but the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) and four major professional sports leagues had actually sued New Jersey in 2012, claiming that legalized sports betting would “irreparably harm amateur and professional sports by fostering suspicion that individual plays and final scores of games may have been influenced by factors other than honest athletic competition.”

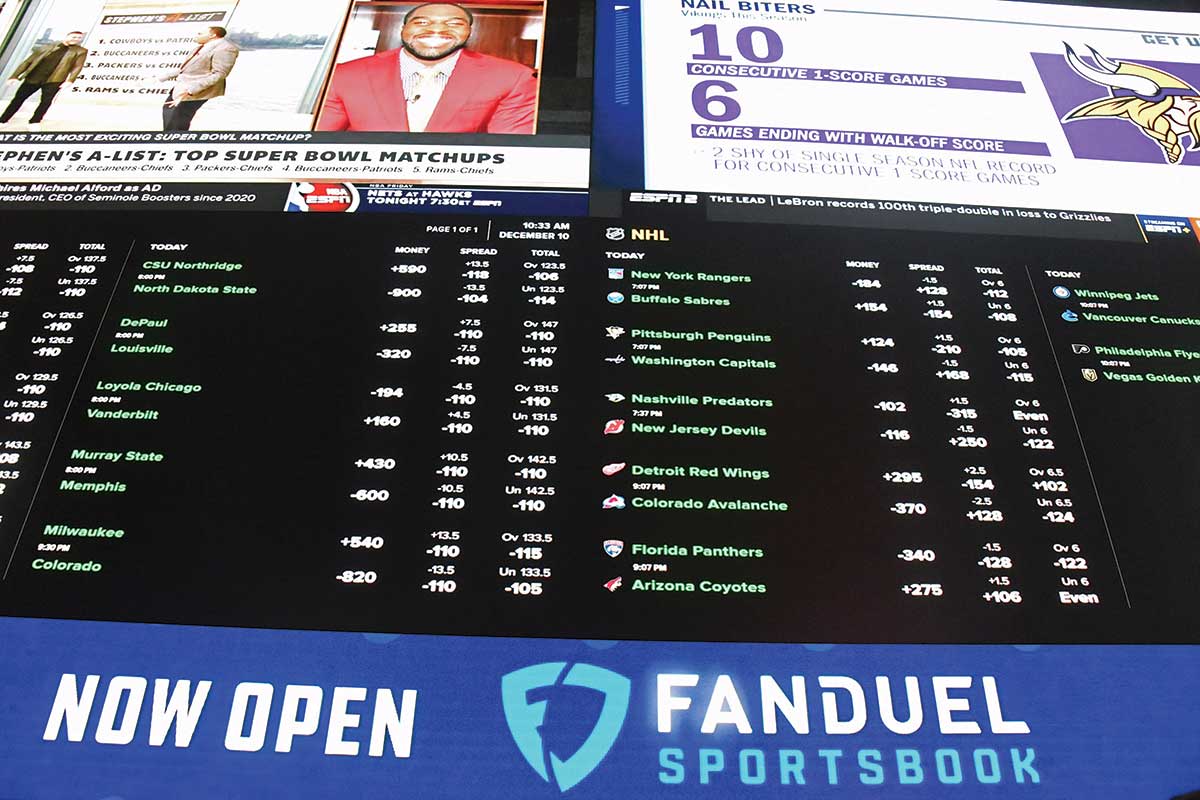

By 2018, those concerns had been brushed off, and the Supreme Court overturned PASPA, leaving the states free to make their own determinations on legalized gambling and sports wagering. As of this writing, legal gaming of some kind is available in all but four US states—Georgia, Hawaii, South Carolina, and Utah—and sports betting is legal in 38 states and the District of Columbia. And in the few short years since the reversal of PASPA, the impact has become obvious.

In February 2025, it was estimated that Americans would legally bet some $1.39 billion on Super Bowl LIX. A month later, an estimated $3.1 billion would be wagered on March Madness, the men’s and women’s college basketball tournaments that remain the most-bet-on events on the calendar. In 2024, legal sports books raked in a record $13.7 billion in total bets, the biggest take since the repeal of PASPA. An industry report from earlier this year was all confidence. “The combination of technological innovation, market expansion, and evolving consumer preferences suggests that 2025 could set new records across all key metrics,” it read.

Here’s another key metric: An estimated 2.5 million adults in the United States (that’s 1 percent of the population) meet the criteria for a “severe” gambling problem, as laid out by the National Council on Problem Gambling. Another 5 to 8 million show signs of “mild or moderate” gambling problems. As many as half of Americans who have sought help for problem gambling have considered suicide. And roughly 20 percent of the people with severe gambling problems have made attempts on their life. Research shows that suicide rates for pathological gamblers are higher than those among people suffering from other addictions, and second only to those among people suffering from major affective disorders like schizophrenia.

“It’s a real public health concern,” says Cait Huble, the director of communications at the National Council on Problem Gambling. “With gambling, it’s seen as a moral condition—and public opinion is very much based on morals—even though we know, chemically, it’s the same as a substance-use disorder in the brain. It’s a diagnosable addiction.”

And yet despite the increase in problem gambling, and despite the billions being taken in by legal gambling operators, it hasn’t really been recognized as a national crisis. “There’s no federal funding for gambling addiction,” Huble says. “Zero dollars.” Instead, funds are allocated at the state level, or sometimes not at all. (Some jurisdictions, such as Montana, Mississippi, and Arkansas, rely on voluntary donations to bankroll resources for problem gambling.) Huble says that problem gambling is seven times more prevalent than substance-use disorders, including alcoholism, yet these afflictions receive 300 times more federal funding. The council’s data shows that, since 2022, calls to the 1-800-GAMBLER helpline have increased by nearly seven times.

From Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” to Martin Scorsese’s Casino, gambling has made for metaphorically rich terrain for storytelling. But that symbolic dimension is withering away. Gambling is no mere allegory for capital acquisition or American avarice; as it becomes more and more ubiquitous, it is those things. Economists have adopted the term casino capitalism to argue that the financial system has started to look like a Vegas den of sin; it’s only recently that gambling has started to become like a global financial system.

The commercialization of sports betting has brought with it a discernible, if difficult to quantify, shift in American life. Sportscasters now talk about “spreads” and “under betters” on broadcasts, as if the gambling implications of a given match (or single play) were not corollary to the action but the point of it. Some big-name sports personalities—from athletes like LeBron James to commentators like ESPN’s Stephen A. Smith—appear in advertisements for sports-book operators, lending credibility to the act of betting while compromising their own. Advertisements lure new customers with offers of enticing sign-up bonuses. While writing this article, I bought a ticket to a concert and was issued $1,000 in credits for an online casino at checkout. On social media, influencers bait bettors into ponying up for their “exclusive picks,” while self-identified “degenerates” merely diarize their own gambling, racking up hundreds of thousands of views for videos with titles like “I Have Not Won in FOREVER!”

During the 2022 Super Bowl showdown between the Cincinnati Bengals and the Los Angeles Rams, the Boston-based gambling platform DraftKings ran an advertisement featuring a black-clad daredevil named Fortune skydiving out of a blimp, riding a motorcycle with Evel Knievel, and watching a young couple get matching tattoos, promoting the idea of betting on sports with the logic “Life’s a gamble.” Later that year, DraftKings’ competitor FanDuel ran a Christmastime ad that imagined what it would be like to wager on various seasonal activities: heated debates, awkward conversations with aunts, whether “grandpa’s in a food coma or a regular coma.” “Everything in life is a bet,” the ad concluded.

The effect is being felt well outside the wide world of professional (and collegiate) sports. Offshore gambling operators offer action on election results and Oscar winners. Online, cryptocurrency-backed “prediction markets” let you bet on, well, pretty much everything. Profit by predicting the outcome of the Romanian presidential election. Or Elon Musk’s number of tweets. Or whether the United States will enter an economic recession in 2025. (As of this writing, the chances are pegged at 40 percent.)

In the run-up to March Madness 2025, the NCAA produced a TV ad. It wasn’t a hype reel for the tournament. Rather, it was a public service spot imploring gamblers not to heckle players. “Only a loser would harass college athletes after losing a bet,” says a stern voice-over. “Don’t be a loser.”

After the 2023 tournament, the NCAA had reported that one in three high-profile student athletes receives harassing or abusive messages from gamblers, mostly on social media. Women basketball players received three times more abusive messages than male players. Coaches, officials, and league administrators were also targets of abuse. “The amount of negative feedback has increased,” says the sportswriter Arif Hasan. “Players are receiving more death threats, receiving a lot more racist commentary, a lot more rancor. The relationship that the average viewer has to sports has changed really dramatically.” As casinos and sports-book operators forge lucrative partnerships with big sports media outlets (ranging from the cable TV giant ESPN to sports-nerd favorites like The Ringer), Hasan has been one of the few sportswriters to report critically on the impact that betting has had on the life of the American sports fan. He has turned down offers of lucrative sponsorships—from banner ads to sponsored posts—from gambling operators, because covering the sports betting industry could violate the non-disparagement agreements that invariably come with that kind of partnership. That said, he’s no teetotaler. “I bet all the time,” he laughs. “You called me an hour after I wrote down $100 in bets for today.” (For the record, I, too, regularly gamble on football games, and occasionally on baseball.)

A lengthy post on Hasan’s popular Substack Wide Left is likely the most thorough accounting of how the growth of legal sports betting has changed the nature of professional sports. In “Has Legalized Gambling Poisoned the Sports Atmosphere?,” Hasan argues that the proliferation of betting fundamentally jeopardizes the integrity of sports on all levels, from individual players and games to entire leagues. (This is, incidentally, the very same argument that the four major leagues used in their 2012 lawsuit against New Jersey’s plan to allow sports gambling there.)

Once upon a time, sports were regarded as the arena for the high-minded ideals of fairness and graciousness connoted by the word sportsmanship. Within the boundaries of a baseball diamond or a football field, in a competition with no meaningful social outcome, an elaborate set of regulations maintained those ideals. The entry of gambling into the arena has, as it were, shifted the goalposts. Poor play has become “flopping,” and even good play is now suspect. Moves that were previously considered savvy, like an NFL running back sliding short of the goal line or an MLB pitcher walking a slugger, can be perceived in the mind of the gambler as deliberate feints. And, of course, the referees are in on it too. “Refs can’t be bad at making calls,” Hasan says. “Now everything is part of this question.”

Sports isn’t the only arena with winners and losers or numbers to crunch. Politics—especially American politics—has long been compared to a horse race, so why shouldn’t it be treated it like one? In 2016, when the British bookmaker Paul Krishnamurty traveled to the US to cover the presidential primaries for Politico, he did just that: Instead of recapping stump speeches, interviewing voters, and conducting the usual work of political reporting, Krishnamurty analyzed the races as a sharp gambler might analyze, well, races. He offered odds on the New Hampshire primary, laid 59-to-1 long-shot odds on Michael Bloomberg’s Democratic candidacy, and “shorted” Ted Cruz in January after the former Republican vice-presidential nominee Sarah Palin threw her support to Donald Trump. When I reached him in the UK in mid-March, he had just finished determining the odds that Democratic minority leader Chuck Schumer would resign.

As a young man, Krishnamurty and his friends would bet on anything: darts, snooker, the next song on the radio, who would speak first in an episode of a daytime soap opera, which pedestrians would make it across a crosswalk first. He calls politics “the sport where knowledge is king.” Polls may not map neatly to reality. Voter behavior is unpredictable. Public opinion is fickle. But politics is otherwise free from the more outright random factors that make sports so exciting (or frustrating). Presidential candidates don’t lose races over a bad bounce.

The year 2016 was a key moment in popularizing politics as a betting market. The US presidential race and the Brexit vote resulted in massive upsets that bucked apparent trends in political polling and offered substantial paydays to anyone who bet the right way. “I won on Brexit,” Krishnamurty boasts, “but Trump completely blindsided me. I didn’t think he’d make it across the finishing line, to be perfectly honest with you. It seemed absurd. But there you go.”

Now Krishnamurty is the political bookmaker for BetOnline, an “offshore” online casino headquartered in Panama City. As an unregulated operator, BetOnline offers gambling action on everything from college basketball and NHL hockey to professional darts and Swiss mixed-doubles badminton, along with a wide array of non-sports options. As of this writing, sharp bettors can place money on next year’s US Senate election in Kentucky, the name the next pope will adopt, the first song Oasis will play on their upcoming reunion tour, and which biblical miracle will be the next to be explained by science (easiest money is currently “Turning water into wine”). “We will price anything,” Krishnamurty says, before adding: “Within tasteful reason.”

Other bookmakers have no such compunctions. The controversial cryptocurrency-backed offshore “prediction” market Polymarket offers action on a series of yes-or-no bets: whether the Ukraine-Russia ceasefire will be violated, whether Egypt and Jordan will accept 100,000-plus Palestinian refugees, whether the US will “take over” Gaza before July, and whether a nuclear weapon will be detonated by June 30.

For his part, Krishnamurty stops short of setting lines on war, terrorism, or anything else in which human lives are at risk. But he has no issues with betting on political outcomes, even though they are instrumental in determining the course of human life. “The rest of the world looks at American politics as absolutely, spectacularly corrupt,” he says. “The idea that we’re corrupting it by having a little bet on the margin of victory in a primary is absurd. Politics, and society, and democracy, have done a pretty good job corrupting themselves.”

Gambling jargon has provided an idiomatic frame for politics at least since the days of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. There’s all that horse track lingo about “dead heats” and contests coming “down to the wire,” or even common figures of speech like “high stakes.” During his disastrous White House tête-à-tête with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, President Trump, perhaps fondly remembering his years as a casino owner, sniffed that Zelensky didn’t “have the cards.”

The current landscape, in which everything is on the proverbial table, goes beyond analogy. Partisans, politicos, and keen actuaries of Elon Musk’s tweeting habits can now put their money where their mouth is. Or, indeed, profit from a kind of emotional arbitrage, as when a friend told me he was betting on Trump to win the US election—not because he liked Trump, but because at least he’d have something to show for it if things went sideways. Yet even this idea, of literally hedging against a preferred outcome, has its basis in sports betting: I’ve heard gamblers talk about betting against their home team, hoping to eke a small material win out of a big symbolic loss.

As the popularity of sports betting, and gambling in general, has snowballed, so have the potential harms. Like most vices, placing bets can be an occasional and careful indulgence, done for the sake of entertainment, which offers a little thrill whether or not you make money on it. But the house, as they say, always wins. As the historian Jonathan Zimmerman wrote in 2012, the gambling industry “redistributes income away from the poor”—not a goal that anyone in the spectrum of American political opinion openly advocates, even those involved in doing it. Yet legalized sports betting has met with little resistance in national and state politics. Gambling, Zimmerman wrote, affronts both Republican ideals of “individual initiative, discipline, and responsibility” and Democratic ones of “fairness and equality.” Meanwhile, its move to the Internet has enjoyed broadly bipartisan support.

Defenders of gamblification—a category that consists mostly of C-suite executives at sports-book companies—claim that wagering on politics or other “real world” outcomes is itself a form of civic engagement. Allowing people to bet on primaries and elections and the date at which ceasefires are violated is not just profitable or fun; it also encourages those people to learn more about the subject at hand. As John Phillips, the CEO of the New Zealand–based online gambling market PredictIt, which allows bettors to buy and trade “shares” in different outcomes, told the British paper The Independent, gambling and prediction wagering is actually “a good thing for democracy.”

There are recent instances in which gambling markets actually proved more accurate than respectable, tried-and-true polling methods. In the weeks before the 2024 US presidential election, Polymarket showed that Donald Trump had a 3 percent edge on Kamala Harris, who was leading in most of the reputable polls. (Trump’s actual margin of victory was closer to 1.5 percent of the popular vote.) There is a certain honesty in how people allocate their money, as opposed to how they might respond to a polling firm interrupting their dinner. Sure, you may have wanted Harris to win. But would you have bet your savings on it?

In the abstract, left and right may converge on the most fundamental principle regarding gambling: that it’s nobody’s business whether or how a person chooses to squander their personal wealth. But the current realities of legal gambling challenge progressive principles of harm reduction, which aim to regulate rather than prohibit vice in order to minimize negative consequences. Today, as those consequences appear to be rising in line with gambling’s explosive growth, the full extent of the damage has yet to be determined. The last substantial nationwide study of gambling and its effects was conducted in 1999, back when you had to call a guy in a leather bomber jacket to lay money on the Super Bowl.

Gamblification embodies two of the most lamentable tendencies of modern life: hyper-speculation on economic assets and widespread social atomization. This expanded, practically frictionless landscape poses new challenges for compulsive gamblers. Groups like Gamblers Anonymous used to tell members to avoid casinos. Nowadays, a digital casino or two can be downloaded to your phone with a few clicks. They would caution against consorting with other gamblers, but with 60 percent of Americans placing a bet in the past year, even that is a practical impossibility. “Gambler”—as in a person who gambles—hardly even qualifies as a discrete, stable identity in a world where everyone gambles and everything is gambling.

Even the way people wager has changed. The growth in sports betting has been directly tied to the increasing popularity of “parlay” bets: Instead of betting on a single outcome, parlays allow gamblers to string together a number of different bets, compounding the odds and the potential payday. In traditional, “straight” sports betting, you might have to wager $100 to win $90. With parlays, gamblers can splash a few dollars down, blindly combine a dozen bets, and cross their fingers, hoping to net thousands (or more) should all of them hit. (A friend, new to sports betting, recently showed me his parlay slip, boasting that he lost his stake by only two outcomes, or “legs.” I gently explained to him that “close” doesn’t really count.)

Gambling apps regularly promote parlays to customers, encouraging these sorts of long-shot bets. Earlier this year, DraftKings launched a subscription model in which bettors could gain access to exclusive parlay bundles and “boosted” odds for $20 a month, which is a bit like paying for the privilege of flushing more money down the toilet. (Why any half-sensible person would trust the exclusive bets directly marketed to them by a casino is another question; when I put it to a DraftKings media rep, they stopped returning my calls.) The indubitable thrill provided by the parlay system, which dispenses with even the minimal patience required of straight betting in favor of a get-rich-quick model, has especially driven the growth in sports betting among millennial and Gen Z gamblers.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Parlay betting follows similar trends in speculative wagering, from novelty cryptocurrencies and the “Wall Street Bets” Reddit community that, in 2021, recruited waves of neophyte retail investors to execute short squeezes on companies like GameStop and AMC. The slower, steadier returns of blue chip investments like IRAs or index funds seem interminable—or are simply unattainable for those whose limited economic opportunities mean they don’t have much capital to invest. The title of a blog entry posted on the website of a “cryptocurrency accelerator community” summed up the promise of parlays and other wildly speculative “investments” in a time of dwindling economic opportunity: “Gen Z’s American Dream: 5 Leg Parlay Your Way to Basic Physiological Needs.” It’s fitting, then, that zoomers have widely adopted the word “bet” (shorthand for “Bet on it”) to mean “yes” or “OK.”

Rob Minnick, the recovering Gen Z gambling addict, has joined his generational cohort of gambling influencers. But he takes a different tack: recording TikTok and YouTube videos warning against the lures of gambling and offering resources and one-on-one counseling to anyone else who is struggling. Of the thousands of messages he says he’s received from those dealing with problem gambling, about half of them, he estimates, are from people under 21.

While his own story—from hardcore fan to daily fantasy player, to confirmed degenerate playing online baccarat in a Paris hotel bathroom, to recovering addict and gambling (or anti-gambling) influencer—offers a measure of hope, Minnick is not especially optimistic, given what he calls the “normalization” of gambling. “What I see is a wave of desperation,” Minnick says. “I think what we’ll end up seeing is people spending the majority of their disposable income on gambling, funding a giant wealth transfer going from the lower and middle classes to the upper class running the system. I think that gambling will destroy the middle class, erase it completely.”

“Get-rich-quick is just part of American culture,” says Hasan, the sportswriter. “It’s embedded in the way we think about success in the United States.” Indeed, gambling itself has an all-American pedigree. British prohibitions on colonial lotteries were among the many irons that stoked the fire of the American Revolution. The so-called sin taxes that states levied on those lotteries even subsidized revolutionary activity. And a marketplace in which nearly anything can become, via wagering, a source of profit represents a kind of ne plus ultra of America’s free-market ideology.

In 1893, The Sun, a New York broadsheet, published a defense of state lotteries. The editorial noted the common refrain, attributed to the English economist Sir William Petty, that lotteries are “a tax on unfortunate, self-conceited fools.” But rather than lamenting their existence, the editorial advocated their expansion. “This verdict of Sir William Petty,” it read, “may almost be thought to-day to offer a most cogent reason for establishing and maintaining public lotteries.… ‘A tax on unfortunate self-conceited fools’ ought to be a very productive tax everywhere.”

Today, 132 years later, lottery sales have fallen by an average of $11.5 million a week in states where sports betting has been legalized. And in states where taxes on sports betting remain low (or nonexistent), legalized bookmaking actually yields a net decrease in public funds. The old justification for public lotteries just doesn’t apply to sports books.

In the end, the “self-conceit” that animates gamblification may be America’s national identity itself. The hometown football game is among the country’s most sacred rituals because the ideals of sportsmanship are meant to be the same as those embodied by the republic: pride in one’s community, the strength of social bonds, the belief in fair play. The sports industry—not to mention the American nation-state—may never have been a realization of those lofty ideals in the first place. But the tremendous sums that casinos and sports books rake in on events like March Madness make it impossible to even keep up the pretense. They seem less like indicators of a free market than massive multibillion-dollar tithings, funneled from some of the poorest Americans to some of the wealthiest.

This, too, seems as all-American as the Super Bowl.

More from The Nation

In the aftermath of this year’s catastrophic fires, architects and urban planners begin to consider how to rebuild.

As the Trump administration tries to remake society along apartheid lines, your vote to stop the assault, however unlikely, is absolutely essential.

Many of those who were loudest in denouncing cancel culture then are now curiously silent in the face of Donald Trump’s assaults on free speech.